Archive for the ‘healthcare costs’ Tag

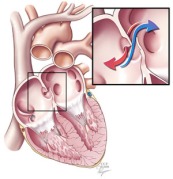

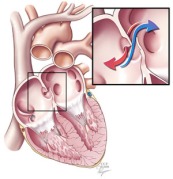

A patent foramen ovale is a defect in the wall between the two sides of the heart that allows the passage of blood and its contents. This course bypasses the lungs. (Courtesy Cleveland Clinic)

One controversial cause of some strokes is a small hole between the two sides of the heart known as a patent foramen ovale. Although rarely symptomatic for patients, this hole allows blood clots that occur in otherwise healthy individuals to bypass the lungs and lodge in critical arteries that serve the brain. In individuals without this defect, these small blood clots would normally lodge in the small vessels of the lungs and typically never lead to a disease state (see note at end for a more complete explanation). Because of the unresolved structural defect, conventional thinking considers these individuals at increased risk for future strokes that remains even after typical stroke prevention strategies.

Kurt Amplatz is an interventional radiologist who has spent his career developing a number of devices to repair these patent foramen ovale and other defects using a catheter-based device that closes the hole with a permanent metal disc. The procedure is similar to cardiac catheterization procedures used for patients with coronary artery disease (e.g., heart attacks).

An Amplatzer occluder deployed on the end of a catheter. (Courtesy St. Jude Medical)

Two recent papers(1,2) in the New England Journal of Medicine report findings from long-term studies designed to demonstrate the expected benefit of using these “Amplatzer” devices versus traditional medical therapies (e.,g., aspirin, Coumadin®, Plavix®). The Journal effectively uses these two studies to demonstrate just how fine a line of improvement may be found with use of the devices and ultimately concludes that true believers and skeptics will likely not be swayed from their opinions by the limited findings of both studies.

What I found most interesting about this recent revival of the debate of catheter-based occlusion devices is the near-zero discussion of the cost component of these devices. The Amplatzer occluder used in these studies was not a one-time quick-fix for these patients but was a supplemental therapy that was often used in conjunction with traditional medical therapies. Although exact pricing is not available, the cost of the device alone adds an additional $3,000-5,000 to the cost of the patient’s care and insurance is usually billed an additional $10,000-$25,000 for the procedure.

With the current evidence, these devices add additional costs and procedural risks to a patient’s care without demonstrating definitive benefit. Addressing the escalating cost-problem in U.S. healthcare starts with regulatory authorities scrutinizing care scenarios such as this one to determine if we are getting value for money in procedural medicine.

Note on blood clots: Venous thromboembolisms are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. However, the specific sequence of events that produces small clots that the human body can easily degrade versus those that cause life-threatening events is poorly understood. Although any blood clot seen in the healthcare setting is typically treated as if it were potentially life-threatening, the general thinking is that small blood clots as in the example given above are somewhat routine in the older population and can resolve spontaneously if not symptomatic.

One of the recent cost-control measures that Medicare has been experimenting with is a planned penalty for hospital systems with high readmissions. For example, if the reimbursement data a hospital files with Medicare shows a higher 30-day readmission rate for patients it previously treated, also called “bouncebacks,” a percentage deduction will be made from all future Medicare payments to that hospital. The basis of this new rule stems from a belief that hospitals with high readmission rates are the result of inadequate care continuity practices and not the result of skewed populations being served. For this post, I will leave aside the many criticisms (e.g., for indigent care hospitals, for population outliers) of the new policy and focus on the innovation trends for helping individual hospitals lower their readmission rates.

Leaving so soon? Most quality experts believe readmissions could be reduced if high-risk patients remained as inpatients longer. (Courtesy Hospital & Health Networks)

The research group that I currently work with at Emory University’s Department of Surgery and Georgia State University’s Andrew Young School of Policy Studies view excessive readmissions as the first signs of correctable errors in the discharge process. These errors can be broadly grouped together as systems-based and decision-related. Systems-based errors are when a patient is not adequately prepared for discharge because of an internal system failure. For example, the process for discharge at a hospital may not properly instruct a patient on the use of home-oxygen prior to discharge. Decision-related errors are when lack of information or external pressure lead to a patient being discharged too early.

Systems-based discharge errors are currently being addressed through traditional quality improvement mechanisms now being applied in the healthcare setting. However, decision-related discharge errors represent an under-explored opportunity for hospitals to reduce their readmission rates. The general thinking is that if physicians can have a more accurate sense of the likelihood of readmission, patients can be discharged at a more appropriate time while not wasting resources by simply holding on to every patient for a longer time period.

Although approaches have varied, the common wisdom to address decision-related discharge errors has been to take advantage of the latest advances in bioinformatics (i.e., healthcare IT) and apply them in real-time to patient discharge decisions. Currently, the most developed commercial solution is Microsoft’s Amalga healthcare information management platform (3M has a similar IT product oriented more toward quality improvement offices). The basic principle of these systems is for algorithm-based analysis of existing patient data to develop and refine predictive tools for use by a physician at the time of discharge of a future patient. For example, as the system collects data on patients who ahad gallbladder surgery it will become increasingly better at predicting which future gallbladder patients will most likely be readmitted. With such information in hand, a surgeon could potentially flag certain patients as high-risk for readmission and manage their discharge more conservatively.

It is important to note that product offerings like Amalga have not been readily adopted by the mainstream healthcare information management community. Critics note that Microsoft has been struggling to establish itself in healthcare IT due to its late entry and lack of a comprehensive product line. Recent moves by Microsoft signal that the company recognizes these vulnerabilities. A 50/50 joint venture called “Caradigm” between Microsoft (an IT and platform leader) and GE Healthcare (an electronic health record industry veteran) aims to capture many of Microsoft’s latest clinical informatics innovations and package them into existing health system platforms.

Currently, these uses of predictive data analysis are in their infancy. To use a term from business innovation theory, we’re in an “era of ferment.” What I find even more interesting than the technical hurdles firms are currently struggling with is the foreseeable problem on the horizon of how we pair technical expertise (healthcare providers) with these predictive tools. This man-machine interface is easy to dismiss, but I believe that successfully addressing it will be the determinant of a successful dominant design.

Disclosure: I currently receive a graduate research stipend from the National Institutes of Health (1RC4AG039071) for work related to surgical patient readmissions and discharge decision-making.